|

|

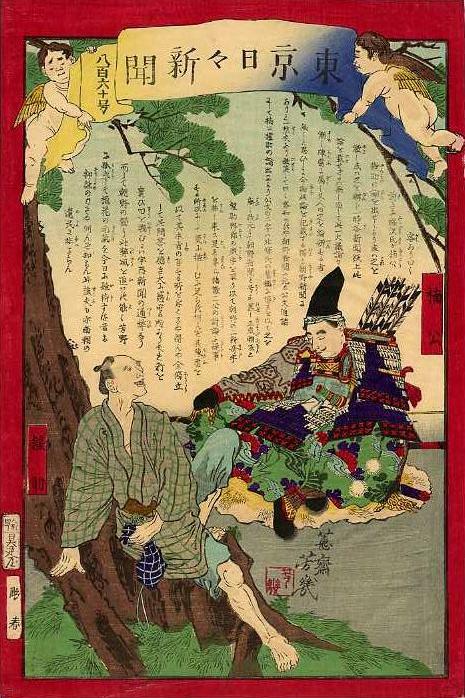

Yosha Bunko

|

Tokyo nichinichi shinbun

No. 860

1874-11-24 (no seal)

Nanko and Gonsuke

Fukuzawa Yukichi on "martyrdom"

The red cartouches identity the protagonists of the story -- Nankō to the right and Gonsuke to the left. The two men never met, at least not in this world, except in discussions of the meanings of their lives as reflected in how they chose to die.

Nankō and Gonsuke crossed paths, long after their deaths, on the pages of Meiji newspapers, following the publication, during the spring of 1874, of Chapters 6 and 7 of Fukuzawa Yukichi's Gakumon no susume (1874-1876) -- usually dubbed "An encouragement of learning" (see "Sources" at end).

Chapters 6 and 7 stirred considerable controversy because -- at a time when political activists were promoting the restoration of imperial rule, and woodblock publishers were commissioning prints that celebrated the sacrifices of loyalist heroes and martyrs -- Fukuzawa was questioning the thoughtless "abandonment of life in defense of right" (Chapter 7, page 69).

Fukuzawa -- citing "maruchirudomu" (martyrdom) as the "word in the west" which signified self-sacrifice (Chapter 7, page 70) -- dared to call wasteful the civil wars that had "killed 10 million people and cost 10 million ryō [in gold]" (ibid., 70) -- and dared to regard as equally futile "the deaths of those loyal retainers who died in battle killing 10,000 enemy, and of this Gonsuke who hanged himself by the neck after losing a single ryō of [his master's] gold" (ibid., 72).

The only true heroes, Fukuzawa concluded, were men like Sakura Sōgorō (circa 1605-1653), the Shimofusa farmer who was executed by the rule of his domain for going to Edo to petition the Shogunate for relief from local taxes (ibid., 72).

Newspaper editors and contributors took issue with Fukuzawa for the way he had criticized the samurai and former samurai who -- during the last years of the Tokugawa era and even at the time he was writing -- had been taking the law into their own hands to assassinate their political enemies -- much as 47 or so retainers of Lord Asano had done in 1703, perhaps not fully aware that, after they had carried out their illegal vendetta, they would be placed under house arrest and ordered to execute themseslves.

In likening the endings of some of the country's most respected popular heroes to "mere dog's death of obstinacy" (kenkai no inujini nomi) -- as he did in a follow-up essay on such matters (Review, page 166) -- Fukuzawa had clearly touched a sensitive spot in public opinion, high and low.

Nankō Gonsuke ron

Most stories in the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun [Tokyo daily news] nishikie series (TNS), though based on reports in the namesake paper (Tonichi), were original stories written expressly for the nishikie and accordingly attributed to their author. The story on this nishikie, though, is unsigned.

The story on the nishikie is in fact a practically verbatim copy of the article in the paper -- judging from the transcription of the newspaper article on Tsuchiya 2000 (Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM), where it is attributed to a certain Yoshino Kōtoku [Yukinori] (吉野幸徳). Yoshino apparently submitted the article as a letter or other such contribution -- and it is a delightful example of tongue-in-cheek praise of Chōya shinbun [Court news], one of Tonichi's rivals, for refusing to join the parade of revering everything new and despising everything old.

The story refers, at the very outset, to Fukuzawa's "Nankō Gonsuke no ron" (commentary on [the deaths of] Nankō and Gonsuke), and how some people attacked and others defended his views, and how all newspapers (新聞紙 shinbunshi) ran all this commentary -- until the great debate staled and no one had any more to say about it -- except Chōya shinbun.

Nankō (楠公) -- literally "Prince Kusunoki" -- is an affectionate reference to Kusunoki Masashige (1294-1336), arguably Japan's most respected hero, who died in battle, taking his own life in the face of defeat while defending the interests of Emperor Go-Daigo (1288-1339).

Gonsuke (権助) was Fukuzawa's archetypal (fictional) servant who, on an errand for his master, lost a gold coin and, to atone for his negligence, "threw his loincloth over the limb of a roadside tree and hanged himself by the neck" (ibid., page 71).

Fukuzawa did not name Kusunoki in Gakumon no susume. "Nankō" appears in a follow-up essay, called "Gakumon no susume no hyō" [A review of An encouragement of learning], which ran in the 7 November 1874 issue of Chōya shinbun, among other papers around this time -- under the playful name "Gokurō Senban (五九樓仙萬) of Keiō Gijuku" -- which clearly alluded to the head-is-bloody-but-unbowed master of the school that would someday became Keio University.

The gist of Yoshino's letter -- which which Tonichi published about two weeks later -- is that Chōya shinbun -- literally meaning "Court news" and originally a conservative voice for the government (as was, for that matter, Tonichi) for the government -- continues to keep the controversy alive because because its name -- "chōya" (朝野) -- reflects both the 朝 (chō) of "Masashige Ason" (正成朝臣) and the 野 (ya) of "Gonsuke Yarō" (権助野郎).

Ason (朝臣) is the Yamato reading of Kusunoki Masashige's rank as a "courtier" -- the Sino-Japanese reading of which is "chōshin" -- meaning literally someone who is loyal to the court.

Yarō (野郎) is an ordinary "bloke" among blokes, if not a country bumpkin -- the "Blow" to the "Joe" of Gonsuke.

While thus poking fun at Tonichi's courtly rival, Yoshino obliquely praises it for not yielding to fashionable opinion.

To revere the new and to despise the old is the common evil of all news (宇内新聞 udai shinbun). And Chōya alone does not follow this evil practice. As for those who, isolated in Yoshino, today maintain the vitality of the cherry blossoms [there], whose power [do they rely on]? The woodcutter, who knows nothing, is probably not a remnant [遺民 wimin, imin; successors, "left people"] of the Southern Court.

The passage alludes to the fact that, in the wake of Kusunoki's defeat, after the victors replaced Emperor Go-Daigo with Emperor Kōmyō, Go-Daigo set up a rival court in the Yoshino mountains in Yamato province (now part of Nara prefecture), south of Heiankyo (Kyoto) in Yamashiro province (now part of Kyoto prefecture), thus beginning the short-lived Northern-Southern Court period (1336-1392) of Japanese political history.

The Nankō-Gonsuke debate was particularly relevant in 1874 because Kusunoki Masashige -- like the fallen heroes of late contemporary (late Tokugawa and early Meiji) civil wars -- was an imperial restorationist -- and every national was capable of dying out of blind loyalty to imperial nation. (WW)

Gakumon no susume

Gakumon no susume [Advancement of learning] was published in seventeen parts between March/April 1872 and November 1876.

Chapter 6 -- "Kokuhō no tafutoki [tōtoki] o ronzu" [Commenting on the value (nobility) of national laws] -- was published in February 1874. It touched upon the fate of those who, like the retainers of Lord Asano, waste their lives, and the lives of others, pursuing and killing their "porichikaruenemi" [political enemies] (pages 55-57).

Chapter 7 -- "Kokumin no shokubun o ronzu" [Commenting on the duties of nationals] -- appeared in March 1874. It referred to "loyal retainers" (忠臣義士) who died in "maruchirudomu" (martyrdom) fighting battles for, or avenging, their lords -- and regarded their deaths on a par with the death of Gonsuke, who killed himself over the loss of a mere coin (pages 70-72).

Such deaths, Fukuzawa argued, were merely self-serving, and contributed nothing to civilization.

Gakumon no susume no hyō

Six months after these two chapters came out, under considerable pressure from the backlash of criticism, Fukuzawa wrote, and published in several newspapers, a follow-up essay called "Gakumon no susume no hyō" [A review of An encouragement of learning]. In this essay, which came out under the name Gokurō Senban (五九樓仙萬), Fukuzawa back peddled a bit, but did not recant his basic thesis that Gonsuke died the death of dog -- and that not a few retainers had also died pointless deaths in the name of loyalty.

The essay was published as a supplement to the 5 November 1974 issue of Yūbin hōchi shinbun (Postal dispatch news) the 7 November 1874 issue of Chōya shinbun, and the 9 November 1874 issue of Yokoyama mainichi shinbun (Yokohama daily news), among other papers.

On the English title

As an English dub for the Japanese title, "An Encouragement of Learning" has echoes of Francis Bacon's "The advancement of learning" (1605). Albert Craig, who referred to the collection of essays in Japanese, introduced the work as "Gakumon no susume (An Invitation to Learning)" (Craig 1968, page 106).

One English translation of the first chapter renders 今余輩の勧むる学問も・・・(ima yohai no susumuru gakumon mo . . .), which appears at the very end of the chapter (Chapter 1, page 18), as "The encouragement of learning that I advocate, too, . . ." (Kiyooka 1960, page 397).

However, the phrase actually translates "The learning we now encourage also . . ." -- which reflects both a verbalization (gakumon o susumu) of the nominal title (gakumon no susume) and the fact that the first chapter was co-authored by Obata Tokujirō (小畑篤次郎 1841-1905).

Sources

All translations of passages from Gakumon no susume and "Gakumon no susume no hyō" in the above citations are mine (William Wetherall). The page numbers in parenthetic attributions refer to the following Japanese edition of Gakumon no susume [An encouragement of learning]. This edition includes "Gakumon no susume no hyō" [A review of An encouragement of learning] (pages 163-175), an overview by Koizumi Shinzō (pages 177-202), and a postscript by Konno Washichi (pages 203-206).

Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901)

Gakumon no susume

[An encouragement of learning]

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1942 (1978, 2006)

206 pages, paperback (Iwanami Bunko Ao 102-3)

1942, 1st printing

1978, 34th printing (revised edition)

2006, 86th printing

The following English translation of Gakumon no susume is useful as a general overview of Fukuzawa's thoughts but is unreliable as a guide to the metaphors he used to express his thoughts.

Fukuzawa Yukichi

[Fukuzawa Yukichi's] An Encouragement of Learning

Translated, with an introduction, by

David Dilworth and Umeyo Hirano

Tokyo: Sophia University, 1969

xv, 128 pages, hardcover

Fukuzawa's grandson, Kiyooka Eiichi, published an English translation of his grandfather's autobiography (1899) in 1934. The 1960 revision has a foreword by Carmen Blacker.

The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa

Revised Translation by Eiichi Kiyooka

With a Foreword by Carmen Blacker

New York: Schocken Books, 1899, 1934, 1960

xxiii, 407 pages, softcover

John Allen Tucker, a professor of Sino-Japanese thought, in the Department of History at East Carolina University, has written both extensively and well on the Nankō-Gonsuke debate. The following essay includes an long list of Japanese sources on this debate.

John Allen Tucker

Yamaga Soko's Seikyō yōroku:

An English Translation and Analysis (Part Two)

Sino-Japanese Studies

Volume 8, Number 2 (May 1996)

Pages 62-85 (24 pages, PDF)

Tucker's citations of Fukuzawa's comments are flawed only by his propensity -- shared by many scholars writing in English -- to "Americanize" and otherwise mangle Japanese metaphors. For example, 国法 (kokuō) and 国民 (kokumin) become "laws of the state" and "citizens" rather than "national laws" and "nationals" (page 70). Note that the Dilworth and Hirano translation correctly renders 国法 as "national laws" but similarly mistranslates 国民 as "citizens" and even "citizens of the nation".

Tucker is especially informative and insightful on how ronin in general came to be romanticized as heroes during the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods. He is today one of the principle writers in English on the significance of the Ako ronin (赤穂義士 Akō gishi) saga in popular culture.

John Allen Tucker

Tokugawa Intellectual History and Prewar Ideology:

The Case of Inoue Tetsujiro, Yamaga Soko, and the Forty-Seven Ronin

Sino-Japanese Studies

Volume 14 (April 2002)

Pages 35-70 (26 pages, PDF)

John Allen Tucker

Yamaga Soko and the Forty-Seven Ronin Vendetta of 1703

Japan, Session 77: Exploring the Ako Incident Controversy

The annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies

Abstracts of the 1997 AAS Annual Meeting

Chicago, Illinois

The following two articles on Fukuzawa are also worth reading. Kinmonth's article is particularly valuable as an examination of the tendency, somewhat seen in Craig's article, to exaggerate Fukuzawa's importance in Meiji intellectual history.

Albert M. Craig

Fukuzawa Yukichi: The Philosophical Foundations of Meiji Nationalism

In: Robert E. Ward, editor

Political Development in Modern Japan

Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, 1968

Pages 99-148

Earl H. Kinmonth

Fukuzawa Reconsidered: Gakumon no Susume and its Audience

The Journal of Asian Studies

Association for Asian Studies

Volume 37, Number 4 (August 1978)

Pages 677-696 (20 pages)

|