|

|

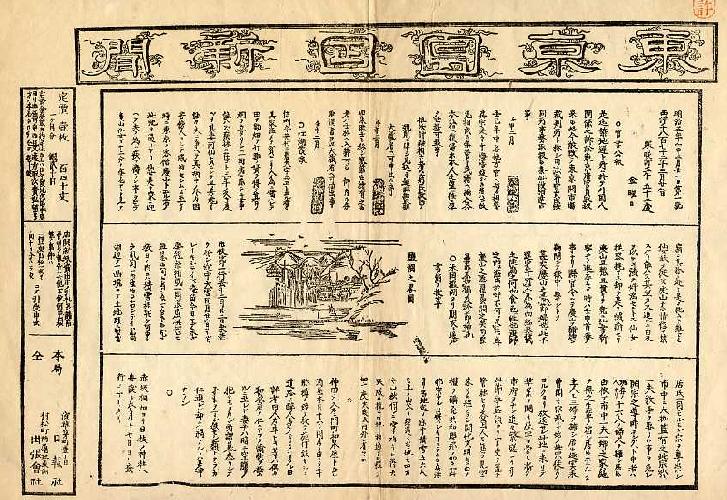

This is the first issue of what students of the history of journalism consider to be Tokyo's first genuine newspaper. It was printed off a block of wood carved from a hand-written copy.

Lunar and solar dates

The upper-right corner, where the paper begins, shows the reign year and the lunar calendar date followed by the issue number, then the "western" year and the solar calendar date, the temperature at noon, and the day of week. This was the last year Japan officially used the lunar calendar.

140 mon each

The issue consisted of only one sheet of paper. What you see in the image is what you got -- for 140 mon [of copper], or 20 me of silver for one month, according to the information in the upper-left corner.

A new currency act was passed the year before, and some gold and silver yen-denominated coins were being minted for use in ports for foreign trade. But in ordinary life people continued to use several older currencies. One "ginme" or "monme of silver" was the equivalent of 3.75 grams of silver, which merchants preferred.

The mints run by the shogunate were just outside the Edo castle, now part of the Imperial Palace. The gold mint was at Kinza, the silver mint at Ginza, and the copper mint at Zeniza, which remain placenames in Tokyo today.

Official briefs

The first two-thirds of the first row are given to short official reports that are written in Japanese so dense it looks like Chinese.

Human-interest column . . .

At the end of the first row are the beginning lines of Koko Sodan [World Stories], a human-interest column about real-life incidents. This first run reports a case about a man who kills his wife.

Reports of murder, suicide, and other such happenings might seem a bit out of place in a paper that began as, and for several years continued to be, a mouthpiece for the government. But take a look at the way this crime report has been written.

. . . begins in Japanese . . . The story begins in a style of Japanese that uses fewer kanji than the official notices. The style, though not as stiff, is not colloquial. And there are no furigana to assist people who may not know how to read well. The nishikie version of Priest Kills Woman is written in a more entertaining, colloquial style. And a number of kanji are provided with furigana. |

Sources: Newspark 2001:9