No. 1155 -- 1876-11-30? Sukiyachō fire Proud standards vying right and leftSeveral fire brigades are fighting a losing battle in a blaze that started late at night and raged till morning. You can count the brigades by their numbered standards -- some engulfed by flames. Yoshitoshi had drawn them all before. And he would draw some again. A book published by the Tokyo Fire Department in 1980, celebrating its centennial anniversary, devoted two pages to the Sukiyabashi fire. According to its account (see source particulars below), the fire broke out at a horse-feed facility around 11:20 on the evening of 29 November 1876. It burned until 7:00 the following morning, spreading through 70,262 tsubo (231,865 square meters), destroying 8,550 buildings, and leaving homeless, injured, or dead over 20,000 people. The feed facility, run by a feed dealer named Suzuki Teizo, was on land Suzuki was renting beyond the outer moat in Sukiyacho 2-chome in Nihonbashi-ku. The fire began in a feed storage facility and escaped through the tile roof of the building. A northwest wind fanned the flames through some 79 blocks (cho) along the moat and through adjacent neighborhoods. A number of theaters were destroyed, including Shintomiza and Nagajimaza. The Australian Mission in Irifunecho, and a substantial part of the foreign settlement, perished in flames. The fire swept between Shinbashi and Kyobashi, leaving practically nothing, and from Hatchobori to as far as Shinkocho in Tsukiji near the bay. |

||||

Transcription and translationThe story in the cartouche reports the origin and spread of the fire in the cartouche on the 3rd sheet ot the YHS-1155 triptych, as shown in the following crop from a 300 dpi scan of the print. Structurally, the story is conveyed in the straight news style familiar today. Graphically, the brusher used the orthography that was common at the time, which will puzzle present-day readers unfamiliar with what are today called "hentai-kana" (変体仮名), meaning the use of cursive forms of the kanji from which kana originated, such as 志 (shi) for し (shi), and "gōryaku-gana" (合略仮名), meaning a single script made by combining and abbreviating two or more kana, such as the "ko" (コ) and "to" (ト) of "koto" (事、こと、コト) and the "yo" (よ) and "ri" (リ) of "yori" (より、ヨリ).

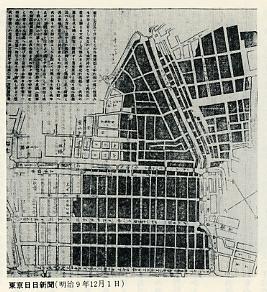

CommentaryThe work was drawn by Taiso Yoshitoshi. His signature followed the text of the story in the cartouche to the left of the banner -- but it is not clear that he was the author. The margins are vermillion -- whereas those of all other known YHS nishikie were purple (accept a few copies that have unpigmented margins, probably the result of an oversight on the part of the printers). The image shown here (from a published image of a copy in the Philadelphia Museum of Art) appear to have been trimmed, but a fragment of the notification (otodoke) date stamp clearly reads Meiji 9 (1876). The margin also appears to include fragments of what may be drawer, publisher, and price disclosures. Triptych scarceVery few copies of the YHS-1155 triptych are known to exist -- judging from its rare mention, and even rarer showing, in publications. The Yosha Bunko copy is in exceptional good condition, compared with the only other copy that I have personally examined -- the Tokyo Shobocho Museum. This copy is probably the copy shown as a black-and-white image in Tokyo Shobocho 1980. The only other copy I have seen in a publication a color image in van den Ing and Schaap 1992, of a copy in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Japanese sourcesThe following three Japanese sources are essential to understanding the position of YHS-1155 in the history of the 1876 Sukiyacho fire. Tokyo Shobocho 1980In 1980, the Tokyo Fire Department published a volume celebrating the first centennial of fire fighting in Tokyo. The book, which was not sold commercially, includes an article and other information on the 1876 Sukiyacho fire (pages 27-28, 616). The Sukiyacho fire article shows a black-and-white image of the YHS-1155 triptych. However, the caption reads simply "Nishikie of Sukiyacho great fire (Yoshitoshi)" (page 28). No other information about the print is given -- no title, no numbers, and no source or ownership attributions. Below the triptych is the following image of a map showing the extent of the fire, attributed to the 1 December 1876 issue of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. Tsuchiya 2000YHS-1155 is listed, but as having an uncertain number, in the table of known news nishikie on Tsuchiya 2000. A parenthetic note in the column for showing the name of the provider of the image on the CD-ROM states that the print was not included in the image database. Tsuchiya did not list the Sukiyacho fire triptych in a similar table in her earlier publication (Tsuchiya 1995), so apparently she ran across a reference to the print but was unable to confirm the paritculars or find a copy. CCMA 2008YHS-1155 is not alluded to in any of the several publications related to news nishikie. The CCMA 2008 exhibition book boasts that all prints are included -- but it misses both YHS-1155 and YHS-832. CCMA also claimed to have discovered prints that turn out to be listed in Tsuchiya's tables. English sourcesThere are several oblique and direct references to YHS-1155 in English sources, and two sources show images of the print. The Sukiyacho fire triptych was shown at a 1992-1993 exhibition called Beauty & Violence: Japanese prints by Yoshitohi, 1839-1892. The image posted here is a scan of a picture of the print in the exhibition catalog compiled by Eric van den Ing and Robert Schaap for the Society for Japanese Arts in The Netherlands (1992:51, see Bibliography). The back matter of the catalog identifies the triptych as No. 1055 in the Yubin hochi shinbun series (1992:114), following Keyes doctoral disseration on Yoshitoshi (1982:407, item 315.59), see Bibliography). The dissertation also shows an image of the print, over a caption which identifies it as No. 1055 (25) (Keyes 1882:138, Plate 21b). Clarification of numbers and datesThe number 1055 seemed too early, given the date of the fire, which occurred a month or so after the rebellions depicted in prints 1127 and 1144. Through a magnifying glass, the number on the right side of the banner appeared to be 1155, and the series number on the left looked like 26 -- another clue, since the series numbers on 1127 and 1144 were 20 and 22 (see YHS two series, three stages). In January and February 2008, I corresponded with John Ittmann, Curator of Prints at Philadelphia Museum of Art, via email, and he confirmed, through a staff member who examined the print, which had been in storage, that the numbers on the title cartouche are in fact 1155 and 26. Moreover, the inscription panel on the left begins with the date Meiji 9th year, 11th month, 29th day, and the bottom left margin contains a printed circular seal that has been trimmed away but still reads Meiji 9th year. Other references to Sukiyacho fire triptychKeyes and Kuwayama 1980, in their discussion of "The Moon through Smoke" (page 96), write that "One of [Yoshitoshi's] most important prints was an 1875 triptych of a recent Tokyo fire whose raging flames are drawn and printed with the same freedom shown here" -- a somewhat inaccurate reference to YHS-1155. YHS-1155 is shown and described in both Keyes 1982 (page 138 figure 21b, and page 407 No. 1055 [315.59]) and van den Ing and Schaap 1992 (page 51 plate 25.59, and page 114 No. 1055). Keyes 1982 links the "Enchu no tsuki" print in the Tsuki hyakushi series with YHS-1155. SukiyabashiAt the time of the fire, Sukiyacho was in an area of Nihonbashi-ku that corresponds to Yaesu 2-chome in present-day Chuo-ku, a short walk from Hibiya, Yurakucho, and Ginza stations. It was reached by a bridge -- Sukiyabashi -- over the outer moat at what had been the Sukiyamon gate to the outer grounds of the former Edo castle. Coming from the castle, one would exit the gate from the Marunouchi side, and cross the bridge to Owaricho on the right and Ginzamachi on the left. The first Sukiyabashi was built in the 6th year of Kan'ei (寛永), circa 1829, on what is now Harumi-dori, the main street through Ginza from the Hibiya intersection at the corner of the present Imperial Palace. The last street-level Sukiyabashi was the arch stone bridge built in 1929 to replace the bridge that was damaged in the 1923 earthquake. Kimi no na waThe arch bridge was the setting for a budding romance in the 1952 radio drama "Kimi no na wa". The drama builds when a man and a woman meet on the bridge after an air raid, and agree to meet there again half a year later -- by which time fate has made their reunion unlikely. A movie came out in 1954, and every ten years or so one TV network or another pairs the couple of the decade in a nostalgic remake. In 1959, the bridge was taken down, and the moat was filled, to build the Tokyo Expressway over where the moat had been. The expressway, most of which is elevated, was finished in time for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The overpass on the Tokyo Expressway, where it crosses Harumi-dori, is called Sukiyabashi. Sukiyabashi is also the name of the interesection on the Ginza side of Harumi-dori -- the first one reaches after walking under the overpass toward Ginza from Hibiya. Sukiyabashi parkBetween the overpass and the interesection, on the right side of the street, is a small patch of green called Sukiyabashi Koen. Leading off Harumi-dori, along the side of the park nearer the intersection, is a narrow side street called Sukiybashi-dori. The park takes barely a minute to walk around. The main attraction of the park, other than a few willow trees, birds, and bird watchers, is a stone marker with the following inscription by Kikuta Kazuo (1908-1972), who wrote "Kimi no na wa" and composed the lyrics for the theme songs (my transliteration and translation).

Other Yoshitoshi firefighter printsYoshitoshi, like most drawers, drew a number of firefighter prints during this lifetime. Most prints did not show fires, but firefighters -- not fighting fires, but displaying their pride in gear and brigade. Firefighters, and their acrobatic performances on high ladders, were major attractions at festivals. Prints showing firefighters as they would dress and act, particularly at festivals, were sold as souvenirs. Prints of the most fabled brigades were as popular as those of the most famous actors, sumo wrestlers, warriers, desperadoes, beauties, and catfish.

Edo firefightersEdo's 64 fire brigades included the "Iroha 48 brigades" and the "Fukagawa 16 brigades". The Iroha brigades consisted of nine groups (1-10 bangumi, no 4-bangumi) totalling 48 brigades (44 hiragana kumi, plus 本, 百, 千, and 万 kumi). The Fukagawa brigades consisted of three groups (South, Central, North) totalling 16 brigades (1 through 16 kumi, including 4-kumi).

The Iroha brigades were set up during the 3rd year of Kyōho (享保) -- circa 1718 -- by Ōoka Tadasuke (大岡忠相 1677-1752), a samurai in the service of the Tokugawa shogunate, better known as Ōoka Echizen no Kami (大岡越前守) from his title as Governor of Echizen. As the magistrate (町奉行 machibugyō) of South district of Edo (the others were Central and North), Ooka enforced the law in the district, but also oversaw other aspects of public safety, including fire prevention. It was in his capacity as a fire marshall that he established Edo's first fire brigades made up of commoners. I-ro-ha"Iroha" refers to a poem that uses all the morae (loosely but incorrectly called "syllables") of the Japanese language, each one time. The original set ("syllabary") consisted of 47 morae (loosely called "syllables") -- created before the innovation of the graph for moraic "n". The poem is written as four 7 / 5 mora couplets.

Transliterated according to present-day orthography -- which reflects moraic changes, voicing, and romanization conventions -- the poem would read -- and structurally translate -- like this. My translation is inspired by B. H. Chamberlain's translation, as cited in Roy Andrew Miller, The Japanese Language, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967, Second Impression, 1970, page 127.

Stigmatized morae and number not usedAt the time the brigades were named, there were 48 morae, hence 48 kana -- those of the original Iroha poem plus "n" (ん). The poem today is sometimes written with "n" (ん) instead of "mu" (む) -- which leaves "mu" (む) without representation. When naming the brigades, four of the 48 morae -- he, ra, hi, and n -- were replaced by "original, principal" (本 hon), "hundred" (百 hyaku), "thousand" (千 sen), and "ten-thousand" (萬 / 万 man). There was no "he" (へ) because it can mean "fart" (屁); no "ra" (ら) because it was cant for something detested and shunned, something which lacks refinement, and may also refer to a penis; no "hi" (ひ) because it can mean "fire" (火); and no "n" (ん) because it lacks euphony, besides which it is not ordinary used by itself but only with, and following, another mora. Presumably "four" (四 shi) was not used as a group name because it is homophonic with "death" (死 shi) -- and hence "四番組" (shi-bangumi) would have suggested "death group". Yet there was a "4th brigade" (四組), possibly because it was pronounced "yongumi". All this is speculation. |