Daikokusha Matsuki Heikichi

The anthropology of an Edo/Tokyo publishing house

By William Wetherall

First posted 3 March 2008

Last updated 27 January 2010

Matsuki Heikichi "Matsuki Daihei" studies | Matsuki and Kiyochika | Decline of Matsuki house | 1890 Daikokuya flyer

Daikokuya Matsuki Heikichi

Daikokuya was a publishing house directed by a succession of men who adopted the name Matsuki Heikichi when they became heads of the house. The publisher flourished during the Meiji period, especially during the last two decades of the 19th century.

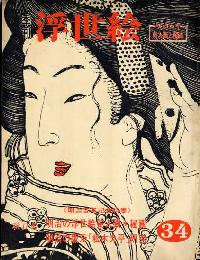

This article consists of two parts -- (1) a brief overview of the rise and decline of this publishing house based mainly on articles in the Fall 1968 issue of the magazine Ukiyoe (Issue 34), and (2) a look at a well-known flyer advertising the Daikokuya publishing house.

"Matsuki Daihei" studiesPublishers typically controlled the projects that resulted in a one-off print or series of prints. Drawers, writers, carvers, and printers were little more than hired hands. The publishers commissioned the more famous drawers and writers, and possibly some of the better carvers, without which no drawing could be transferred to blocks and printed. While publishers stood to make more money by using the most popular drawers and best craftsmen, nothing would have been produced without their orchestration, which included distribution and sales.

Ukiyoe 1968-34The journal Ukiyoe, while focussing on drawers and their works, has occasionally run articles about publishers and others who materially produced woodblock prints. Issue 64 (Fall 1968), which celebrated the 100th year of the Meiji Restoration, led with a feature about Meiji-era bijinga (beauty pictures) and higa (secret pictures). The second feature, though, was on the Matsuki Daihei family of publishers, which was closely associated with the career of Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), one of the last major drawers of the Meiji era. Fuller particulars regarding this issue are shown in its review as Ukiyoe 1968-34 under Publishers in the Drawings section of the Bibliography feature of this website. Matsuki Daihei featureThe Matsuki Daihei feature was titled "Meiji no hanmoto: 'Matsuki Daihei' kenkyu" or "Meiji publisher: 'Matsuki Daihei' studies". The feature included the following three articles. 1. Biography of Matsuki Daihei family by Yoshida Susugu (pages 52-61) 2. Two-page list, compiled by Yoshida Susugu, of nishikie the Matsuki publishing house printed from the Ansei period beginning circa 1854 through 1904 (pages 61-62) 3. Recollections of Matsuki Daihei compiled by Nishina Yusuke (pages 63-65) |

Matsuki and KiyochikaMatsuki Heikichi, commonly known as Daihei, was the inherited name of the head of the Daikokuya publishing house, which had been in business for over a century when the Meiji era began and Edo became Tokyo in 1868. The fortunes of the Daikokuya rose and fell in the Meiji period with the popularity of Kiyochika's drawings, which including many landscapes, but also woodblock-printed cartoons, including two series of political cartoons with stories written by a well-known satirist during the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 and the Russo-Japanese of 1904-1905. Matsuki Heikichi the 4th (d1891, age 56), whose signature name was Agarie (tentative reading of 東江), was the third son of a banner retainer from Fukui. Agarie's wife, Toyo (died 1919), is said to have been a geigi. (Ukiyoe 34:59) Toyo, too, was from Fukui, and apparently knew a number of leading politicians and entrepreneurs from the prefecture, including Itō Hirobumi (1841-1909), Japan's first prime minister. Toyo is reputed to have been a proud, strong, intelligent woman, and as the matron of the publishing house, it was she who took care of Kiyochika. (Yoshida 1968, Ukiyoe 34, page 59) Having no children, Agarie adopted Ishikawa Heishichi, the third son of a man who boasted descendancy from Minamoto no Yorichika, a mid-Heian general. Heishichi was 13 (14) in 1885, and Agarie was 50, when Heishichi formally succeeded to the title of Matsuki Heikichi the 5th (1871-1931). (Shiina 1968, Ukiyoe 34, page 63) Toyo had something to do with taking care of Hirata Saku (1882-1947), her niece, who became Heishichi's wife. (Yoshida 1968, Ukiyoe 34, page 59) Matsuki Heikichi the 4th introduced Kiyochika's earliest works in the mid 1870s. Heishichi was 19 (21) and Kiyochika 44 (45) when Agarie passed away in 1891. (Yoshida 1968, Ukiyoe 34, page 59; see following note on ages). Note on agesIn the above graphs, the ages shown first are my estimates, based on the birth and death dates shown in a geneological chart of the Daikokuya family (Ukiyoe 34:60). The ages shown in parentheses are those shown in the source (Ukiyoe 34). The source, for example, states that Heishichi and Kiyochika were 21 and 45 when Agarie died, and that Agarie was 56 at the time of his death. However, these ages are based on reckoning gestation as one year, and counting the year in which one is born as the second year of life. The geneological chart gives the following birth and death dates. The [bracketed remarks] are mine.

|

Decline of Matsuki house

Heishichi and Saku had a son, but he did not wish to succeed his father. In the wake of Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Heishichi, sick and discouraged, chose not to rebuild the business, which had started to decline long before Kiyochika's death in 1915.

Heishichi died in 1931, and his son died two years later (1898-1933). Saku passed away two years after World War II, and her daughter-in-law -- born in 1900 -- followed her in 1953, leaving a son and a daughter, who were alive at the time Yoshida Susugu wrote his informative article. (WW)

1890 Daikokuya flyerDaikokuya is the subject of the best-known Meiji flyer advertising a publishing house. Yoshida Susugu's article shows a black-and-white image of the flyer, and transcribes and paraphrases most of its text. Here I will introduce other details on the print, which can easily be confirmed on the high resolution scan, in the following database, of the copy in the print in the Nishigaki Bunko collection at the University of Waseda Library. The copped and cropped image shown to the right is also fairly legible.

The flyer, woodblock printed on an oban sheet (roughly B4), was published in 1890, the year before Matsuki Heikichi the 4th passed away. The left side of the flyer reads 書物 錦絵 問屋 大黒屋 松木平吉 (shomotsu / nishikie / toiya Daikokuya Mastsuki Heikichi) or "written matter / color pictures / publisher and seller Daikokuya Matsuki Heikichi". The term "written matter" (書物 shomotsu) referred to more serious books, typically non-fiction or classics, as opposed to "local books" (地本 jihon), which meant books published in Edo of a lighter and more popular sort, mostly fictional stories, usually illustrated. The term "toiya" (問屋) -- read "-doiya" when combined with words like "shomotsu-" or "jihon-" -- referred to a business, person, or "house" (問 ya) engaged in work "regarding" (問 toi) the handling if not also the making of something, in this case printed matter. Most publishers also sold and distributed their products. The flyer shows a picture of a "benie-uri" -- a vendor (uri) of "benie" -- originally a woodblock print of a black-lined picture which had been colored by hand. From about the middle of the Edo period, the term referred to a vendor who walked around with a bamboo pole strung with pictures of beauties, actors, and warriors. The large characters on the gable read "Yoshiwara" (吉原) -- the famed pleasure quarters of Edo/Tokyo. On the blue cartouche immediately below the gable are smaller characters the "Great-gate entrance" (大門口 Oomonguchi) to the pleasure quarters. The name "Mirua" (三浦) appears on the noren at the entrance to the house being advertised by the model. Down the side of the base of the box below the model run calligraphy reading "Elegant beni colored figure pictures" (風流紅彩色姿絵 furyu beni saishiki sugatae) -- a common reference to nishikie depicting beautiful women, particularly famous geigi. The right seal at the top gives the year as 2550, counting from the first year of the reign of Emperor Jinmu. The left seal the same year in the Meiji era -- Meiji 23 -- 1890 -- the year Constitution came into effect. The story to the right, apparently written by Matsuki Heikichi the 4th, narrates the history of the Daikokuya publishing house, which has "succeeded for 5 generations since opening at its present location the first year of Meiwa (circa 1764), and carried out its operations while upholding the ethnical principles for a hundred and some tens of years . . . ." I missed a catalog offering of this flyer by a Kanda print shop in 2007. There was a frenzy of requests, and it went to the first caller. The print shows the intimate relationship between woodblock publishing and tea-house entertainment -- while the Matsuki Heikichi household exemplifies how families reached across class lines to provide themselves with successor heirs. Waseda Library write-upA write-up on this flyer, posted in the Nishigaki Bunko section of Waseda Library's old and rare book collection, identifies it as that of a 書物錦絵問屋 ("Book and Nishiki-e Wholesaler"), and identifies the producer as 大黒屋 (松木平吉) ("Daikokuya (Matsumoto [sic = Matsuki] Heikichi)"). The other particulars in the Waseda write-up are as follows (retrieved 27 June 2009).

The English version is accurate enough -- although 欧米 (Ō-Bei) is more generally "Europe and America". |