| Almanac of news nishikie and related topics | |||||

| Introduction | Newspapers | News nishikie | Other nishikie | Who's who | Glossary |

Here you will find a variety of information about the people involved in the production of the newspapers and nishikie presented on this website.

If immortality is a measure of success in life, then many of the people who contributed to the making of news nishikie were failures. We know nothing, or very little, about most of the writers, carvers, and publishers. Many of the drawers, too, have been forgotten in reference books and footnotes.

Those who signed their names to works are at least attributed. Doing most of the detail work for the signature drawers and carvers, though, were unnamed apprentices and helpers who today would be duly acknowledged in fine print in accordance with their union contract. Everyone who breathed air in the workshop would be credited. Tea-servers, floor-sweepers, brow-sweat-wipers, night-soil removers. The providers of the wood, pigments, washi. Trademark signs everywhere. And a disclaimer to the effect that The publisher is not responsible for any corruption of morals that may result from viewing too many nishikie.

The purpose of this Who's Who is to share whatever information has been discovered about, especially, the little people. The big people have had any number of books written about them. If the number of biographies and studies of influence are any guide, Yoshitoshi is big fish, and Yoshiiku is small fry. For this reason, an attempt has been made to reveal all that is known about Yoshiiku -- the road less traveled by art historians -- though inevitably more will be written about Yoshitoshi.

| Publishers |

|

Woodblock publishers produced all manner of printed matter, from newsprints and advertising flyers to books and color prints. They employed or commissioned the artisans who did the technical work, from drawing and writing to carving and printing, and oversaw sales and distribution. |

|

Gusokuya 具足屋 |

Gusokuya Kahee 具足屋嘉兵衛 Fukuda Kahee 福田嘉兵衛 (d1885) Fukuda Kumajiro 福田熊次郎 |

|

Tokyo woodblock publisher. Shop located in Ningyocho.

Gusokuya produced all of the first-runs of Yoshiiku's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie. The shop name was that of the Fukuda family, beginning with Fukuda Sahee. Kahee was the 2nd generation head of the family, and Kumajiro the family, and the name of his son Kumajiro was the 3rd. Kumajiro's name appears on Gusokuya prints published after the promulgation of new regulations in September 1875 required woodblock prints to show the legal names and addresses of the drawers and publishers. |

|

|

Hirooka Kosuke 1829-1918 広岡幸助 |

Hiroko 広幸 (name as publisher) |

|

Hirooka Kosuke was the hanmoto Hiroko, under which seal he published numerous nishikie, including many drawn by Yoshiiku with stories written by Sansantei Arindo. Hirooka later joined Jono Denpei, Nishida Densuke, and Ochiai Yoshiiku in 1872 to become one of the founders of Nipposha and Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. Like Nishida, he had been an employee of the Tsuji family. Also like Nishida and Jono, and possibly Yoshiiku, he had helped Fukuchi Gen'ichiro publish Koko shinbun in 1868. |

|

|

Kinshodo 錦昇堂 |

Ebisuya Shoshichi 恵比寿屋庄七 [ Kumagaya Shoshichi 熊谷庄七 ??? ] |

|

Ignore following notes. Tokyo woodblock publisher. In operation since at least 1855 to at least late 1870s. |

|

|

Tsujibun 辻文 |

Tsujiokaya Bunsuke 辻岡屋文助 (publisher) [ Tsujioka Fumihiko 辻岡文彦 (publisher) ??? ] |

| An Edo/Tokyo woodblock publisher located in Yokoyamacho 3-2. Operated between at least 1864-1879. All Tonichi news nishikie were originally published by Gusokuya. However, some prints were reissued by Tsujibun, which apparently bought blocks of popular prints from Gusokuya, recarved the publishers name. Some Tsujibun editions also replaced the original carver's name by "horiko" (ホリ工), which means just "carver". Tsujibun was one of the largest woodblock publication dealers in Edo/Tokyo during the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods. | |

| Drawers |

|

Drawers sketched pictures for all manner of woodblock printed matter, including color prints and illustrated books. In the case of colored prints, they also designed the color schemes, which determined how many blocks had to be carved and the order the blocks had to be printed in order to produce the designed colors. |

|

Hayakawa Shosan 1850-1892 早川松山 |

Hayakawa Tokunosuke 早川徳之助 (real name) |

| Pupil of Kawanabe Kyosai. (WW) | |

|

Kaburaki Kiyokata 1878-1972 鏑木清方 |

Jono Ken'ichi 條野健一 (real name) |

| Kaburaki Kiyokata was born Jono Ken'ichi, the son of Jono Denpei, better known as the gesaku writer Sansantei Arindo. Through his father's close association with Yoshitoshi, Ken'ichi came to know the drawer and aspire to be like him. In 1886, Jono Denpei employed Yoshitoshi as an illustrator for the Yamato shinbun, and he also put the young Ken'ichi to work for the paper as an illustrator. The year Yoshitoshi died, Ken'ichi became a student of Yoshitoshi's disciple Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908) and went on to became one of Japan's better known Utagawa/Yoshitoshi-style Nihonga drawers. Kaburaki passed the baton to Ito Shinsui 伊東深水 (1898-1972). (WW) | |

|

Kobayashi Eitaku 1843-1890 小林永濯 |

Sensai Eitaku 鮮斎永濯 (other name) |

| Kobayashi Eitaku did the illustrations for Kakushu shinbun zukai no uchi news nishikie. He is mainly known for his satirical drawings and illustrations for children's books. He was an illustrator for the Yokohama mainichi shinbun. He also drew many of the pictures for the early "crepe paper books" (chirimenbon) for children written by Hasegawa Takejiro (1853-1936), translated by Hasegawa's missionary friends, and published by Kobunsha. These color woodblock print books are among the earliest examples of translated children's literature in Japan. Eitaku's adopted son and pupil was the drawer Kobayashi Eiko (1868-1933). (WW) | |

|

Sadanobu II 1848-1940 二代貞信 |

Hasegawa Sadanobu II 二代長谷川貞信 (full name) Hasegawa Konobu 長谷川小信 (former name) Hasegawa Tokutaro 長谷川徳太郎 (real name) |

|

Drawer for Yubin hochi shinbun nishikiga and several other Osaka news nishikie. First son of Hasegawa Sadanobu (c1809-1879), aka Sadanobu I (Shodai Sadanobu 初代貞信). Signed prints as Konobu (小信) from 1863-1875. Succeeded to his father's name as Sadanobu II from 1875-1910, hence the declaration "Konobu changed to 2nd generation Sadanobu" (小信改二代貞信) on some of his 1875 prints. See Nichinichi shinbun (NS 日々新聞) and Osaka nichinichi shinbunshi (ONSs 大阪日々新聞紙) on the Osaka news nishikie galleries page for examples. Hasegawa Sadanobu's 2nd son Sadakichi (貞吉 1859−1886) also appears to have used the name Konobu (小信). |

|

|

Shigehiro 茂廣 |

菊水茂廣 Kikusui Shigehiro ? 柳櫻茂廣 Ryuo Shigehiro ? |

|

Drawer for Osaka Nichinichi Shinbun news nishikie. Teamed with Ryūō Sanjin [Sennin], who wrote the stories. Ryūō (柳櫻) may have been Shigehiro himself (Tsuchiya 1995:42). Francis Minvielle asks, "Was Shigehiro a pun for Hiroshige?" Possibly -- at least to the ear. And given Hiroshige's fame, "Shigehiro" might have drawn smiles. The derivation of Shigehiro's name is not clear. Either component -- "shige" or "hiro" -- could have come from a mentor, and both were very common. But graphically, while the "hiro" of Hiroshige and Shigehiro was the same -- 廣 also written 広 -- the "shige" were different -- 重 for Hiroshige (廣重) and 茂 for Shigehiro (茂廣). According to Japanese Prints, "Shigehiro Shugansai was a printmaker of the Osaka School, a pupil of Nagasaki Shigeharu. He drew specialized news woodblock prints for Osaka Nichinichi Shinbun." "Shigehiro Shugansai" refers to "Shūgansai Shigehiro" (秀丸斎重広). Nagasaki Shigeharu (長崎重春 1802-1852/3) was born Yamaguchi Yasuhide (山口安秀) in Hizen province. He went to Ōsaka around 1820 and became a student of both Ganjōsai Kunihiro (丸丈斎国広 bd unknown) and Yanagawa Shigenobu (柳川重信 1787-1833). He first used names like Nagasaki Kunishige (長崎国重), Baigansai Kunishige (梅丸斎国重), and Takigawa Kunishige (瀧川国重), in which "Kunishige" (and "Baigansai") reflected his links Ganjōsai Kunihiro. He later went by Ryūsai Shigeharu (柳窗重春、柳斎重春), which reflected his links with Yanagawa Shigenobu. |

|

|

Toshinobu 1857-1886 年信 |

Yamazaki Tokusaburō 山崎徳三郎 |

| As his name suggests, Toshinobu was a student of Yoshitoshi (芳年). Legally he was Yamazaki Tokusaburō (山崎徳三郎). He was 13 when he began to study under Yoshitoshi and 20 or 21 in 1878, when he drew 12 or 13 nishikie based on Chōya shinbun stories. The Seinan War, which took place the year before, inspired numerous prints depicting scenes from the war, including about 30 prints by Toshinobu. At the time, Toshinobu was also working as an illustrator for Ch??ya shinbun, the name sake of the nishikie series. The prints were numbered according to the issues of the papers from which their stories were adopted, but they came out several months later, and in random order, and were probably independently published as souvenirs. Though regarded as one of Yoshitoshi's most promising students, from about 1880 Toshinobu and Yoshitoshi had a falling out, partly over Toshinobu's drinking and carousing. Attempts by a third party to mend the relationship ultimately failed, as Toshinobu continued to be unstable. He reportedly even walked off with some of Yoshitoshi's manga sketches, and apparently a wanted notice was published in a newspaper under Yoshitoshi's name. Toshinobu was only 28 or 29 when he died of pneumonia and meningitis in 1886. Yoshifuji lampooned several of Yoshiiku's Tonichi news nishikie in crude look-alikes usually called Tokyo nichinichi shinwa but at times called Nichinichi. He also drew the usual variety of genre prints, including sumo prints, and Yokohama prints depiciting aliens, and even a print showing an alien being thrown by a sumo wrestler. His most remarkable Yokohama alien prints have title cartouches with romanization. | |

|

Yoshifuji 1828-1887 芳藤 |

Ippōsai Yoshifuji 一鵬斎芳藤 Omochae no Yoshifuji おもちゃ絵の芳藤 (self-styled nickname meaning "Yoshifuji of plaything pictures" or "Yoshifuji who draws game pictures") |

| Yoshifuji lampooned several of Yoshiiku's Tonichi news nishikie in crude look-alikes usually called Tokyo nichinichi shinwa but at times called Nichinichi. He also drew the usual variety of genre prints, including sumo prints, and Yokohama prints depiciting aliens, and even a print showing an alien being thrown by a sumo wrestler. His most remarkable Yokohama alien prints have title cartouches with romanization. | |

|

Yoshiiku 1833-1904 芳幾 |

Ochiai Yoshiiku 落合芳幾 (full name) Ochiai Ikujiro 落合幾次郎 (real name) Ikkeisai 一惠齋 (most common signature name) Keisai 惠齋 (恵斎) (another signature name) |

||

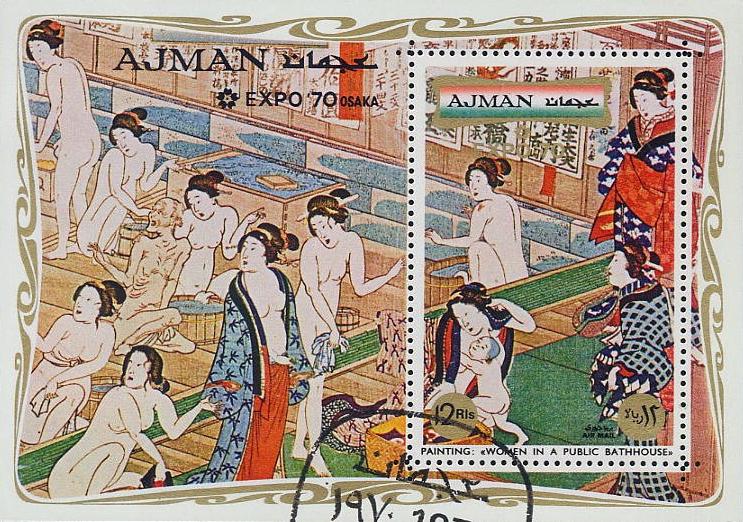

Late Edo- and Meiji-era printmaker and illustrator. Principal illustrator and drawer for Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. His most common signatures were Keisai Yoshiiku and Ikkeisai Yoshiiku. Other names included Utagawa Yoshiiku, Ochiai Ikujiro, Chokaro, Sharakusai [Sairakusai], and Keiami. Yoshiiku was the Edo-born son of the proprietor of a teahouse in the Yoshiwara entertainment district. He was apprenticed to a pawnshop but then became a pupil of the woodblock drawer Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), hence some of Yoshiiku's other names. One student of Yoshitoshi later wrote that Yoshiiku bullied the somewhat younger Yoshitoshi, who the aging Kuniyoshi treated like a son. Whether or not this allegation has any foundation, there would have been a natural rivalry between two drawers, particlarly coming up in the same school, and competing for the master's (and later society's) recognition. In the late 1860s, Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi collaborated on the production of the Eimei nijuhasshuku series. And throughout the next two decades, they often shared the same writers and publishers. It was not the sort of world in which they could have let whatever bitterness might have come between them at times to get in the way of their work. See translation-in-progress of Higuchi Futaba on Ochiai Yoshiiku for more information on Yoshiiku's life. Yoshiiku achieved philatelic immortality in 1970 when the Emirate of Ajman, in commemoration of Expo '70 Osaka, issued a set of ukiyoe stamps, including a 12-ri airmail stamp on a miniature sheet showing part of Yoshiiku's Kurabekoshi Yuki no Yanagi Yu (Women in a Public Bathhouse). (WW) |

|||

|

Yoshikage 1858-1922 芳景 |

Goto Yoshikage 後藤芳景 (full name) Goto Tokujiro 後藤徳次郎 (real name) Hosai 豊斎, Kawazu Yoshikage 川津芳景 |

|

Osaka drawer and illustrator. Drew some prints for Nichinichi shinbun, an Osaka news nishikie series. Though Yoshikage lived in Tokyo for a while, he was born and worked mostly in Osaka, where he was a student of Sasaki Yoshitaki. (Tsuchiya 2000 Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM) |

|

|

Yoshimitsu 1850-1891 芳光 |

Sasaki Yoshimitsu 笹木芳光 (full name) Nakai Kazo 中井嘉蔵 (real name) |

|

Osaka drawer. Drew for Osaka nishikie shinbun and other Osaka news nishikie. Younger brother of Sasaki Yoshitaki. Yoshimitsu, like Yoshitaki, studied under Nakajima Yoshiume (Hobai) and then under Yoshitaki. Yoshimitsu took the Sasaki name instead of Yoshitaki, who returned to being Nakai. (Tsuchiya 2000 Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM) |

|

|

Yoshitaki 1841-1899 芳瀧 |

Sasaki Yoshitaki 笹木芳瀧 (name from 1875) Nakai Yoshitaki 中井芳瀧 (later name) Nakai Tsunejiro (Kojiro) 中井恒次郎 (real name) Ichiyosai 一養斎, Ichiyotei 一養亭, Yosui 養水, Hogyoku 豊玉, Jueido 寿栄堂, Satonoya 里の家 |

|

Osaka drawer and writer. Drew and wrote many of the stories in the Osaka nishikiga shinbun, Osaka nishikie shinwa, Kanzen choaku nishikiga shinbun, and Shinbun zukai series of Osaka news nishikie. Yoshitaki was born Nakai Tsunejiro (Kojiro) in Shimizucho in Osaka in 1841 as the older son of Nakai Genbei (中井源兵衛). He took the name of the Sasaki family on his father's side from 1875, the year practically all his news nishikie drawings appeared. Later, his younger brother Yoshimitsu assumed the Sasaki name and Yoshitaki returned to being Nakai. From age 12 to 15, Yoshitaki was a student of Nakajima Yoshiume (Hobai) (中島芳梅), who had studied under Kuniyoshi. His own students included Goto Yoshikage, Kawasaki Kyosen (1877-1942), and Sasaki Yotsimitsu (his younger brother). He moved to Kyoto in 1880, and in 1885 he moved to Sakai in Osaka prefecture, where he died in 1899. He is buried at Nanshuji on Ryukozan in Sakai. Sources Tsuchiya 1995, Tsuchiya 2000 (Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM), and other Japanese sources. Note Kawasaki Kyosen (川崎巨泉) was born Kawasaki Suekichi (川崎末吉) in Sakai in 1877. According to a source attributed to Roger Keyes, Kawasaki was Yoshitaki's son. Whether a son by birth or adoption is not clear, as I have not yet seen the attributed source: Roger Keyes and Keiko Mizushima, The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints (A Collection of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Japanese Woodblock Prints in the Philadelphia Museum of Art), Boston: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973, 334 pages. |

|

|

Yoshitora Dates unknown 芳虎 |

Nagashima Toragorō (Toranosuke, Toranorō) 永島辰五郎 (辰之助、辰三郎) Ichimōsai 一猛斎, Mōsai 孟斎, Kinchōrō 錦朝楼 |

|

Yoshitora, a disciple of Kuniyoshi, drew numerous prints from about 1840 to 1881 -- the last 3 decades of the Edo period and the first decade or so of the Meiji period. He was Kuniyoshi's oldest pupil, but in the 4th intercalary month of the 2nd year of Kaei (嘉永2年閏4月), about May-June 1849, he was expelled from Kuniyoshi's studio following his arrest and punishment for a satirical drawing the government viewed as seditious. Yoshitora was one of the most prolific wood block designers and illustrators of the Bakumatsu and early Meiji periods. He drew numerous one-off prints and series featuring landscapes, townscapes, beauties, warriors, actors, and sumo wrestlers. But he is probably best known for his portraits of foreigners in Yokohama. See, for example, Gaikoku jinbutsu zukushi on this website. |

|

|

Yoshitoshi 1839-1892 芳年 |

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 月岡芳年 (earlier full name) Taiso Yoshitoshi 大蘇芳年 (later full name) |

|

Late Edo- and Meiji-era printmaker and illustrator. Principal illustrator and drawer for Yubin hochi shinbun and then Yamato shinbun. One of the most versatile drawers of his day and arguably the last great woodblock drawer with roots in the Edo period, Yoshitoshi was born Owariya Yonejiro, and went by a number of the other names -- including Tsukioka and, later, Taiso -- during his illustrious, somewhat unstable, but hardly tragic life. Yoshitoshi illustrated some the early works of the gesaku writer Sansantei Arindo, who's real name was Jono Denpei. The drawer and writer collaborated on a number of projects, in including Eimei nijuhasshuku (1866). Jono founded Tokyo nichinichi shinbun with Yoshitoshi's rival Yoshiiku, and when Jono and Yoshiiku began creating nishikie based on Tonichi stories in 1874, Yoshitoshi became the principle drawer nishikie that recycled stories from Tonichi's rival Yubin hochi shinbun. A decade later, in 1886 when he launched Yamato shinbun, Jono hired Yoshitoshi as the paper's principle illustrator and as the drawer for its supplementary Kinsei jinbutsu shi (Accounts of contemporary personalities) series. Cathrine E. Lowther, of Sinister Designs in Canada, has the most interesting introduction to Yoshitoshi and his works on the Internet. |

||

| Writers |

|

Writers told the stories that appeared on printed matter. They wrote the stories themselves, or narrated the stories while someone transcribed them. Some stories were carved from texts brushed by the writer, while others were carved from texts prepared by a scribe or calligrapher. Some drawers wrote their own stories. |

|

Hokiyama Kageo 甫喜山景雄 |

|

|

Jono Denpei 1832-1902 條野伝平 |

Sansantei Arindo

山々亭有人 (pen name) Saigiku 採菊 (pen name) |

|||

Born in Edo in 1832, by his late teens he had decided to become a writer of gesaku stories. He published his first story in 1860, and during the 1860s first Yoshiiku, then Yoshitoshi, were doing illustrations for some of his books. Jono, a literary friend of Fukuchi Gen'ichiro, was behind the start-ups of several papers, beginning with Fukuchi's Koko Shinbun in 1868. He teamed up with Yoshiiku and others to launch the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun in 1872, and in 1874 he again teamed with Yoshiiku to produce the news nishikie that flew Tonichi's banner. He went on to launch the Keisatsu Shinbun [Police News] and the Yamato shinbun [Yamato News] in 1884 and 1886. Yoshitoshi did some of the illustrations for Yamato shinbun, and Jono also put his Kanda-born son Ken'ichi to work as an illustrator. Through Yoshitoshi's influence, Ken'ichi went on to become the Nihonga drawer Kaburaki Kiyokata (1878-1972). It was, as the saying goes, a small world. Jono continued to write fiction until his death in 1902. (Compiled from Newspark 2001:82-84, 2-2) Read more about Jono on Waifu Seijuro's Jono Saigiku site (Japanese) |

||||

|

Kagen, Kagendō Dates unknown 花源、花源堂 |

Maeda Kijirō 前田喜次郎 |

|

Writer of stories on many Ōsaka news nishikie prints drawn by Sadanobu. Some other prints by Sadanobu show his name as Maeda Kijirō, an Ōsaka woodblock print and book publisher. |

|

|

Kanagaki Robun 1829-1894 仮名垣魯文 |

Nozaki Bunzō 野崎文蔵 (real name) 假名垣魯文 (older graph for "ka") 神奈垣魯文 (alternate graphing of "kana") |

Kanagaki Robun"Kanagaki" reflects Robun's profession as a "kana writer" (仮名書き kanagaki). "Robun" combines two kanji in the names of his mentor, the writer and playwright Hanagasa Bunkyō (花笠文京 1785-1860), also known as Rosuke (魯介). Robun was 14 when he came under Hanagusa's tutelage and 15 when he adopted the name Ei Robun (英魯文). Robun was one of the most important writers of both reportage and fiction in the late Edo and early Meiji periods. He worked with illustrators like Kawanabe Kyosai, Yoshiiku, Yoshitoshi, Yoshitora, Yoshitoyo, Hiroshige III, Yoshu Chikanobu, and Toyohara Kunichika, often in collaboration with two or more drawers at the same time. To give just two examples: Robun teamed with Yoshiiku, Yoshitoshi, and Yoshitora in Kogane no hana neko mekazura (黄金花猫目鬘), published in 13 fascicles between 1863 and 1868 by Shōrindō (松林堂), and with Kawanabe, Yoshiiku, and Hiroshige III in Seiyo dochu hizakurige (西洋道中膝栗毛), published in 30 fascicles between 1870 and 1876 by Bankyūkaku (萬笈閣) and others. Robun was also closely associated with other writers of the gesaku genre, including Takabatake Ransen, a Tonichi writer who wrote most of the stories that accompanied Yoshiiku's pictures on Gusokuya's TNS nishikie. Like a number of other writers of entertaining stories, Robun became involved in the rapidly growing news industry. On 1 November 1875, in Yokohama where he was then living, he helped found Kanayomi shinbun (仮名読新聞) or "Kana-reading news" -- a title which implied that the news could be read in kana because all kanji were printed with kana readings. In 1877 the paper moved to Tokyo and its name was shortened and simplified to just Kanayomi (かなよみ). Seiyodochu hizakurige (1870-1876)Robun is equally remembered for "Bankoku kōkai / Seiyō dōchū hizakurige" (萬国航海 西洋道中膝栗毛) -- "A voyage to all countries: Knees for chestnut hair on the way along the western ocean". The 15 volumes of this comic saga were published between 1870 and 1876 in 30 fascicles, illustrated by Ikkeisai Yoshiiku, Ryūsai Hiroshige [Hiroshige III], and Shōjō Kyōsai (Kawanabe Kyōsai). The title was inspired by a series of comical novels by Jippensha Ikku (十返舎一九 1765-1831) beginning with "Tōkaidōchū hizakurige" (東海道中膝栗毛) or "Knees for chestnut hair on the way [to towns] along the eastern sea" -- i.e., "Walking [instead of riding a chestnut horse] along the Tokkaido [from Edo to Kyoto]". knees for chestnut hair (hizakurige) means walking, rather than riding astride a common chestnut horse. The expression is often morphed into "shanks [shanks's, shank's, shanks] mare [nag, pony]" in various dialects of English, where such idioms mean to use one's own shanks (legs) instead of relying on a horse or horse-drawn vehicle. Robun puts the grandson's of Ippensha's familar protagonists -- Yajirobee (Yaji) and Kitahachi (Kita) -- and sends them off from Yokohama to get in trouble -- instead of in post towns along the Tokaido -- "in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Saigon, Singapore, Ceylon, Suez, Cairo, Alexandra, Marseilles, Paris, Gibraltar, and South Hampton" among other places on their way to see the Great London Exposition (Kobayashi in Kanagaki 1997:9). There were world fairs in London in 1862 and Paris in 1867, and another was scheduled for Wien in 1873. The London fair was attended by members of a Tokugawa mission then traveling the world to observe other countries and gather information. Aguranabe (1871-1872)Robun's best known work is a parody called Ushiya zōdan / Aguranabe or "Beef shop small talk / Cross-legged [at a beef] pot]. See Kanagaki Robun's Aguranabe: Beef, sake, news, and Westophiles in Early Meiji Japan for commentary and partial translation of the first story in this work. See On "nishikie shinbun" for Robun's take-off on reading "news" in "newspapers" while eating beef. Eshinbun Nipponchi (1874)In 1874, as Kanagaki Robun (神奈垣魯文), he and Kawanabe Kyosai teamed to publish Eshinbun Nipponchi (絵新聞日本地) or "Picture news Japonchi" -- which Kyoto International Manga Museum (京都国際マンガミュージアム Kyoto Kokusai Manga Myuujiamu) calls the first "manga magazine" (漫画雑誌) to be published in Japan by Japanese. The magazine and its name were inspired by Japan Punch, a news magazine published and illustrated by the English artist and cartoonist Charles Wirgman (1832-1891), in Yokohama, from 1862 to 1887. "Ponchi" (ポンチ) was then a buzzword in Japanese meaning the English style of satire typified by cartoons and other comical drawings in Japan Punch -- hence the expression "ponchie" (ポンチ絵) or "punch picture" -- and hence, also, "Nipponchi" (Japonchi) as a playful allusion to "Japan Punch". The pun was kept alive in Nipponchi (日ポン地), a satirical cartoon magazine occasionally put out as an extra edition of Japan's first monthly graphic magazine Fuzoku gaho (風俗画報 Fūzoku gahō), published between 1889 and 1916 by Toyodo (東陽堂 Tōyōdō) in Kanda. |

|

|

Onkokudo Ryugin 温克堂龍吟 |

Okada Jisuke 岡田治助 (real name) |

| (Tsuchiya 1995:22) | |

|

San'yutei Encho 1839-1900 三遊亭円朝 |

Izubuchi Jirokichi 出淵治朗吉 (real name) | |

Rakugo storyteller and writer. When stenography was developed for Japanese in the late 19th century, many of his orated stories were transcribed and became bestsellers. Wrote many of the stories on Yoshitoshi's Yubin hochi shinbun nishikie. |

||

|

Shorin Hakuen II 1834-1905 松林伯円 二代 |

Wakabayashi Yoshiyuki 若林義行 (real name) |

| Actor and narrator. He narrated many of the stories for Yoshitoshi's Yubin hochi shinbun nishikie and performed some the stories on stage. | |

|

Takabatake Ransen 1838-1885 高畠藍泉 |

Tentendo

転々堂 (pen name) Takabatake Heisaburo 高畠瓶三郎 (real name) Ryūtei Tanehiko III (三世柳亭種彦) (posthumous) |

|

Takabatake Ransen was a gesaku writer and journalist. Though not born until 1838 (Tenpo 9-4-19, 12 May 1838), he is said to have been a student of Ryūtei Tanehiko (柳亭種彦 1783-1842). He is also said to have received the succession name Tanehiko II (二世柳亭種彦) in 1882 (Meiji 15) -- though reportedly this name had been claimed by a deceased older disciple, Ryūtei Senka (笠亭仙果 1804-1868), and Takabatake, who died in 1885 (Meiji 18-11-18, 18 November 1885), was apparently content with being socially called Tanehiko III (Suzuki Kōzō, 1928, as cited by Takagi Gen, 2004, and on his website). Takabatake joined Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (Tonichi) shortly after its start in 1872. He wrote most of the stories for Gusokuya's TNS nishikie series based on Tonichi articles, and collaborated with Yoshiiku, one of Tonichi's founders and the drawer of the TNS series, in launching the illustrated Hiragana eiri shinbun in 1875. He used numerous names as a fiction and non-fiction writer -- including, on his TNS stories, Tentendo, Tentendo Shujin, Tentendo Dondon, Dondon, and even Tentendo Ransen. His first and best-known work of gesaku fiction was Kaika hyaku monogatari (怪化百物語) or "One-hundred tales of mystification". For more about Ransen and this work, see TNS-876 Mysterious incidents. |

|

| Carvers |

|

Carvers -- aka cutters -- chiselled and otherwise finessed the sketches of the drawers and the brushed texts of the stories told by the writers, into the grains of the blocks of wood. |

|

Watanabe Horiei 渡辺彫栄 |

渡辺長栄 Watanabe Choei |

| Carver for Gusokuya. Carved for both Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi. | |

| Others |

|

This section includes people who were not directly involved with the production of news nishikie, but who were involved in the publishing of the newspapers related to news nishikie, or otherwise figure in the history of news nishikie. |

|

John Reddie Black 1827-1880 ジョン・レディー・ブラック |

|

|

Black, a British subject from Australia, came to the Foreign Settlement in Yokohama in 1863. He became an editor for The Japan Herald and The Japan Gazette and spent some time in China. On 3 June 1870 (Meiji 3-5-1) he began publishing The Far East, a fortnightly paper in English that featured general news, editorials, and entertainment, but also articles and photographs of everyday life. The paper covered Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan. The 30 September 1874 issue of The Far East, a photo-illustrated newspaper published in Yokohama by the Scottish British Australian journalist John Black Reddie, is said to have carried the first news report in English about the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie series (Tsuchiya 2002:105). The article in question, entitled "Art in Japan", introduced TNS-512, the Tonichi nishikie which shows and tells how Kurako defended her father Amano against robbers (Tsuchiya in Kinoshita and Yoshimi 1999:104, n5; see also Meech-Pekark 1986:216, 242 n16). Two years before this, Black became a catalyst in the government's decision to permit Jono Denpei, Yoshiiku, Nishida Densuke, and Hirooka Kosuke to launch the print edition of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. There are several versions of the story, but all agree that the government was in a bind, having decided to give Black permission to publish its official reports, and not wanting a foreigner to monopolize their distribution. Whether Black published the first issue of Nisshin shinji shi (日新真事誌) on Meiji 5-2-8 (16 March 1872) [Internet chronology], or on Meiji 5-3-17 (24 April 1872) [Okitsu 1999:224], the government, which had been slow to respond to Jono's proposal, now gave him the green light, and Tonichi's first issue came out on Meiji 5-2-21 (29 March 1872), either a couple of weeks before or after Black's paper. Black was a bit of a thorn in the government's side. He was highly cooperative and even worked for the government, yet he also took advantage of his status as a British subject who sometimes got his way because he was sheltered by extraterroriality. By 1875, however, control of his paper had been transferred to a Japanese national, and the following year Black was prevented from starting another paper. A interesting footnote to this story is that Black's son, Henry Black (1858-1923), became Japanese in 1893, a year before Lafcadio Hearn followed the same path, through a provision of an 1873 proclamation that allowed a foreign man to become Japanese by being adopted as the husband of a Japanese woman. He divorced the woman, whose name was Ishii, a year later. Henry Black is better known in Japan as the rakugo storyteller Kairakutei Burakku. Raised mostly in Japan, he was totally bilingual and spent his adult life as an entertainer, and the first to produce a phonograph recording of rakugo. The arc for those interested in news nishikie is that Kairakutei's friendship with the narrator Shorin Hakuen from the late 1879s led to his career as a hanashika storyteller. He was also a friend and rival of San'yutei Encho. Both Shorin and San'yutei narrated stories for several of Yoshitoshi's Yubin hochi shinbun nishikie. (McArthur 1992:YYY, Okitsu 1997:XXX; Kojima 1997:ZZZ) |

|

|

Eto Shinpei 1834-1874 江藤V平 |

|

|

Eto Shinpei, from a prominent samurai family in Saga, participated in the Satsuma-Choshu alliance to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate. He held several posts in the new imperial government, and was Minister of Justice in 1873 when he resigned his post to protest the government's rejection Saigo Takamori's proposal to subjugate Korea. Eto was among those who advocated that the capital be moved from Kyoto to Edo. He became the Minister of Justice in 1872, and oversaw the creation of a new police system and the enactment of the Kaitei Ritsurei criminal code, an expedient revision of Tokugawa codes to serve the new state until it was ready to draft a new penal code. After quitting his post in 1873, he stayed around Tokyo to support a movement to create a more representative government. In early 1874, however, he returned to Saga, and as the head of a group of disgruntled samurai who called themselves the Seikanto (Chastise Korea Party), he led them against imperial forces in what is called the Saga Rebellion (Saga no Eki). Quickly defeated, Eto fled to Kochi, but was found and sent back to Saga, and immediately tried and executed. He was cleared of the charges against him by the amnesty declared in celebration of the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution in 1889. Cathrine E. Lowther nicely describes the dynamics of Eto's plight in her comment on Yoshitoshi's study of Eto in Kinsei jinbutsu shi.

Tokyo nichinichi shinbun reported in its 28 April 1874 issue that the heads of Eto and former 前秋田権令島義男 Shima Yoshitake were publicly exposed (Ono 1972:150). Eto's severed head is putatively the subject of a photograph reproduced in a study of kawaraban and newspapers (Nishimaki 1878.3:37). Eto's plight was also the subject of a couple of news nishikie, which make it clear that he didn't die on the field. To be continued. |

||

|

Joseph Heco 1836-1897 ジョセフ・ヒコ |

Hamada Hikozo 浜田彦蔵 (original name) Hamada Kikotaro 浜田彦太郎 (another name) |

|

Hamada Hikozo was rescued by an American ship in 1850 with other crewmen after drifting in his step-father's boat for two months. He was eventually taken to the United States and educated in English. While still in his teens, he had an opportunity to meet president Franklin Pierce. He was baptised as Joseph Heco and became an American citizen in 1858. In 1859 he returned to Japan as an American and worked as an interpretor with a US delegation. Back in America in 1861, met Secretary of State John Seward, and shook the hand of Abraham Lincoln. During the Civil War, Heco returned to Japan, and in 1864 he published Shinbunshi, soon renamed Kaigai shinbun, Yokohama's first Japanese-language newspaper, with the help of Kishida Ginko. At the start of the Meiji period he went into business in Nagasaki, but later settled in Tokyo, where he served in the Ministry of Finance. Heco published his memoirs, The Narrative of a Japanese, edited by James Murdoch, in 1895. He died two years after and was (and presumably still is) buried in Aoyama Cemetery in the section then reserved for foreigners. |

|

|

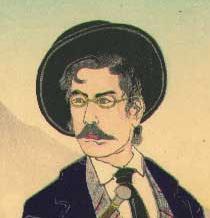

Fukuchi Gen'ichiro 1841-1906 福地源一郎 |

Fukuchi Ochi 福地桜痴 (pen name) | ||||

Born in Nagasaki in 1841, Fukuchi was to became one of the most active and well-travelled reformers of Meiji Japan. He was a student of Dutch and interpreted for Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866) in 1859. He and Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901), among other young linguists who discovered that English was the new wave, accompanied Japan's first overseas mission to Europe in 1862. He studied law, literature and drama, and practically everything else it seems, and opened a language school. Fukuchi made another trip to Europe before publishing a periodical called Koko Shinbun (World News), which got him arrested, in 1868. In 1870 he entered the Finance Ministry and went to the United States with Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909) and other young reformists, and in 1871 he accompanied the Iwakura mission to the United States and Europe. Back in Japan in 1873, Fukuchi quit his government post, and in 1874 he joined the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, which his journalist friends had started while he was overseas. He was also recruited by Tonichi's rival, Yubin hochi shinbun, but went to Tonichi on the condition that they make him to control the paper as chief editor. Fukuchi promptly began writing editorials, in which he expressed all manner of opinions, mostly fairly conservataive, which kept in constant trouble with the more reform-minded authorities in the government, and invited the dismay of the more liberal opinionists at Yubin hochi shinbun. At the outbreak of the Seinan War, Fukuchi dispatched himself to Kyushu and covered the battles. Click on the picture to the right to see a fuller copy of a study of Fukuchi as a war correspondent drawn by Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) and published 16 October 1885. An 1877 Kagoshima shinbun nishikie triptych called Nipposha's Glory shows Fukuchi conveying his observations directly to Emperor Meiji. In 1888, tired of the politics of journalism, he quit the Tonichi to return to what he loved most -- literature and drama. He designed and opened the Kabukiza in 1888-1889 and became its chief playwright. When he died in 1906 at age 65, he left many novels and plays. Satoko, his wife since 1861, followed him in 1919. (Compiled from Huffman 1980:203-105 and Newspark 2001:2-3--2-4) See Huffman's Politics of the Meiji Press: The Life of Fukuchi Gen'ichiro for more about this amazing pioneer. |

|||||

|

Kishida Ginko 1833-1905 岸田吟香 |

Kishida Ginjiro 岸田銀次郎 (real name) | ||

Kishida Ginko was one of most colorful and worldly Bakumatsu and Meiji personalities. He lived in Shanghai for two years in the late 1860s while helping Hepburn publish the first Japanese-English dictionary to appear in Japan. He was particularly interested in Japan-China relations, and typical of many internationalists, he was also a nationalist. As a businessman who manufactured and sold an eye medicine in both Japan and China, he fully believed in the "fukoku kyohei" (rich nation, strong army) motto of the Meiji state. Ginko, as he is often called, joined the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun as a journalist in 1873. Over the objections of Saigo Tsugumichi, who led a punitive expedition to Taiwan in 1874, Ginko accompanied the expedition as a Tonichi reporter, becoming not only Japan's first foreign correspondent, but also the country's first "embedded" journalist. |

|||

|

Nishida Densuke 1838-1910 西田伝助 |

Nishida Rinnosuke 西田林之助 (real name) Nishida Kinha 西田菫坡 (another name) |

|

The manager of a lending library (kashihon'ya) run by Tsujibun Den'emon at the time he joined Jono Denpei and Ochiai Yoshiiku to start the newspaper company which published Tokyo nichinichi shinbun. Nishida ran the business side while Jono did the writing and editing and Yoshiiku drew illustrations. Nishida retired from Nipposha in 1891. See more about Nishida on the Kido Jibutsu site (Japanese). |

||

|

Saigo Takamori 1827-1877 西郷隆盛 |

|

|

Saigo Tsugumichi 1843-1902 西郷従道 |

|

|

Text forthcoming. |

||

|

Tsuji Den'emon 辻伝右衛門 |

|

|

Tsuji Den'emon was an official at Ginza, the silver mint in front of Edo Castle, now the Imperial Palace. When the mint closed, he opened a lending library (kashihon'ya) in the Moto-Osaka-cho area of Nihonbashi. Nishida Densuke was the head clerk of this shop and Hirooka Kosuke was also an employee of the Tsuji family. Both Nishida and Hirooka, and Jono, and possibly Yoshiiku, had helped Fukuchi Gen'ichiro publish Koko shinbun in 1868. |

|